4 Kochs took genes, money in different directions

Washington (AP) — They are an outsized force in modern American politics, the best-known brand of the big money era, yet still something of a mystery to those who cash their checks.

Meet the Koch brothers. (Pronounced like the cola.)

Perhaps the first thing you need to know is that there are four of them.

Charles is the steady, driven one. He's grounded in the Kansas soil of their birth.

David is his outgoing younger brother. He's a New Yorker now and pronounces himself forever changed by a near-death experience.

William is David's free-spirited twin, a self-described contrarian whose pursuits beyond business include sailing, collecting things and suing people, including his brothers.

And then there's Frederick, the oldest, who's as likely to turn up in Monte Carlo as at his apartment on New York's Fifth Avenue. He doesn't have much to do with the rest of the lot.

They're all fabulously wealthy, all donate lavishly to charity, all tall — Frederick is the shortest at 6-foot-2 — and all are prostate cancer survivors. Beyond that, there are plenty of differences.

Charles and David are the billionaire businessmen who are pouring millions into politics. Bill and Freddie, as they're known in the family, cut their ties to the family business decades ago and don't display the same passion to change the world.

As Bill sizes up his siblings during an interview with The Associated Press: "David and I like off-color jokes, Freddie likes more sophisticated jokes." Charles? "Charles likes golf."

___

Charles and David, in sync on business and politics, are miles apart in geography and style.

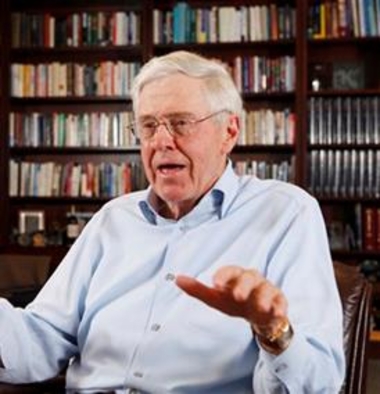

Charles is the white-haired alpha male at the helm of Koch Industries. Midwestern through and through, the 78-year-old still walks up four flights of stairs to work at Koch headquarters in Wichita, Kansas, each morning and eats lunch in the company cafeteria.

After building Koch Industries into the nation's second-largest private company, he turned his business philosophy into a book, "The Science of Success."

"He's the most focused person I've ever met in my life," says Koch general counsel Mark Holden. "A purpose-driven life, that's Charles."

Charles wrote in The Wall Street Journal this spring that in recent years he's seen "the need to also engage in the political process."

And how.

He and David have created a sprawling network of groups working to promote free-market views, eliminate government regulations, fight President Barack Obama's health care law, oppose an increase in the minimum wage, shift control of the Senate to Republicans and oust Democrats from office.

___

David, a Koch executive vice president and board member, keeps a higher profile. He ran for vice president as a Libertarian ticket in 1980 and chairs Americans For Prosperity Foundation, a tax-exempt corner of the brothers' network.

At 74, with a distinctive bray of a laugh and an aw-shucks manner, David is literally a fixture in New York. His name is splashed across many of his charitable causes. Among them: the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center and the forthcoming David H. Koch Center for ambulatory care at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. (He committed $100 million to each).

David's giving escalated after two searing experiences: his survival in a 1991 plane crash that killed 34 people, and a subsequent diagnosis of prostate cancer that left him believing he didn't have long to live. (His brothers all began regular testing, and caught their cancers much earlier.)

"When you're the only one who survived in the front of the plane and everyone else died — yeah, you think, 'My God, the good Lord spared me for some greater purpose,'" David once said.

David is equally passionate about politics, once telling a reporter for the liberal blog ThinkProgress, when asked if he was proud of Americans for Prosperity, "You bet I am, man oh man."

___

And what of Bill and Freddie — the other Koch brother and the other other Koch brother?

Bill, 74, worked for Koch Industries in the 1970s, but grew frustrated with what he saw as Charles' autocratic management style and the corporate money his brother put into politics.

What came next played out over two decades: Bill and Freddie tried unsuccessfully to oust Charles as chief executive. Bill got fired. Charles and David bought out their brothers for a combined $800 million. Bill had second thoughts and sued for more. Charles and David won.

"Financially, we probably made a bad deal," Bill says, then adds: "In my life, I'm happier than I ever have been when I was working at Koch Industries. I'm my own person."

Today, he runs his own energy company, Oxbow Carbon LLC and ranks 122nd on Forbes' richest-people list. He's stopped collecting artwork because he's "run out of wall space." But he's still suing people, spending more than $25 million on lawsuits against dealers he's accused of selling fake wine.

Freddie, who turns 81 on Tuesday, loves restoring castles and historical houses.

by Nancy Benac, Associated Press. Associated Press writer Philip Elliott and News Researcher Judy Ausuebel in New York contributed to this report.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

The Gayly – August 25, 2014 @ 10:25am