"After Louie": An AIDS survivor, barely surviving

by Mark King

Guest Contributor

Sam Cooper, a shell-shocked gay veteran of the 1980’s, has invited Braeden, a much younger man, out for a hamburger after their sexual tryst. Braeden has been mindlessly chattering about his life and friends and how he negotiates casual sex outside his relationship. Hookups carry no more weight for Braeden than the phone he uses to find them.

When he was younger, Sam pointedly responds to the pleasant but unequipped Braeden, all of Sam’s friends were dying. He went to funerals twice a week. Sam delivers these facts with a satisfied but weary glare across the table.

Braeden looks wounded. An untouchable trump card has been played. He can only hang his head in an obligatory reverence. There is an unbridgeable gulf between them and more to the point, between the generations of gay men they represent.

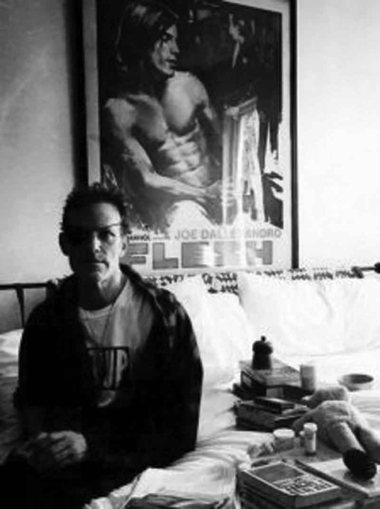

The telling conversation happens somewhere in the first half of After Louie. Director Vincent Gagliostro’s semi-autobiographical film stars Alan Cumming as a haunted New York City artist trying to come to grips with his tragic past. What a shame that, to appreciate this scene of cross-generational grappling, one must endure the surrounding 90 minutes of this defiantly sullen story.

The problem is Cumming’s performance. It isn’t just willfully morose, it is frantically morose. Cumming stalks through the film, spreading Sam’s misery to every other character like the disease that has defined Sam’s life.

Whether having sex with Braeden or while in the company of other artists or what’s left of his friends, Sam suffocates everyone in his path with resentments and memories of the plague years. Sam, as played by Cumming, is an insufferable relic of sorrow.

Cumming embodies all this through the cigarettes he sucks with more primal hunger than an addict hitting a crack pipe. Truly, Cumming should thank the two fingers he employs to melodramatically grasp his cigarette. They’re doing all the work.

After Louie presents AIDS trauma as a kind of relay race. Louie, an unseen friend long dead from AIDS, is mourned by William, who appears in some old home movies that chronicle Louie’s demise. William has since died as well and is now mourned by Sam, who cannot seem to find anyone to take the sad baton of grief.

Zachary Booth plays young Braeden with a soulful earnestness. He has the trickiest role. While Sam once fought valiantly for something beyond Braeden’s comprehension. Braeden reaps the rewards by engaging in transactional sex within a much less perilous world.

For all of Braeden’s talk of sexual freedom, it is reduced to coming home late at night and stripping quietly in the dark, careful not to awaken the man he claims to love. Booth almost convinces us to empathize with Braeden and his meager values.

Fleeting moments of grace are included in After Louie, usually when Sam is nowhere in sight. A random meeting on the street between two elderly men, once lovers, leads to their passionate reunion over tea and the strains of opera on the record player. Their quaint make-out session stands in stark relief to their younger counterparts, grinding and scruffing their days away.

The most buoyancy in After Louie is provided by actor David Drake, playing William. In his brief scenes, Drake imbues William with a kindness and generosity of spirit that exists nowhere else in the story. William may be dead, but he is the most fully alive character in the film.

William’s moments in After Louie are the ones I choose to remember. There is a lesson in his death grip on joy and gratitude even as he faces oblivion. Buried somewhere in the melancholy, After Louie is an opportunity for us all to learn from it.

After Louie is making the rounds of film festivals now and will hopefully find a broader home soon on streaming or cable. Find out more by visiting the film’s the film’s website. Criticism aside, After Louie deserves to be seen and understood.

Mark S. King is an award-winning writer (www.marksking.com) and HIV/AIDS advocate who has been involved in HIV causes since testing positive in 1985. He lives in Baltimore with his husband Michael.

Copyright The Gayly – November 15, 2017 @ 7:10 a.m. CST.