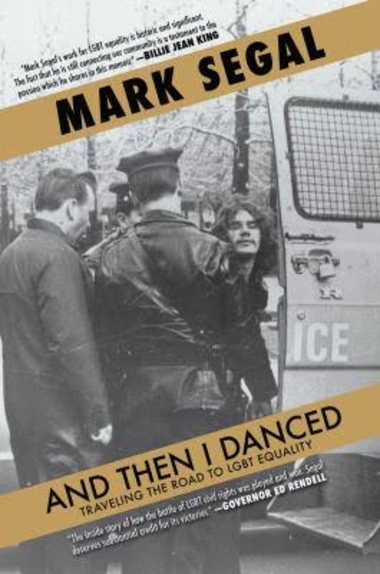

And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality

Review by Gena Hymowech

And Then I Danced is more than a memoir; it’s a revelation. In writing about his life, Mark Segal not only shines a light on his own achievements but on those of others, including Marty Robinson and Craig Rodwell. These names, like Segal’s, are not as well-publicized as they should be, and that’s a huge part of why this book is so vital.

Equally important is how Segal shatters mistaken beliefs about queer history.

Growing up poor and Jewish in a Philadelphia housing project, discriminated against, and living in conditions that are beyond frustrating; Segal experiences the perfect training ground for life as a gay activist. In just a few lines, he perfectly describes the unique heartbreak being poor brings. His mother has taken him to buy a toy after his father practically had a nervous breakdown because he wasn’t able to give Segal something he wanted:

As we entered Wilson Park, [Mom] asked if I liked my toy. I reached into the bag and my train was gone. I said nothing. Seeing my reaction, she took the bag and found the hole in the bottom through which my toy had fallen out. She just started to cry. Watching my mother cry after all that had occurred that day, I wanted to cry and yell as well, but instead I got sick to my stomach. I just stood there in silence, awash in guilt.

As a boy, Segal is tempted mightily by the sexy men’s fashion section of the Sears and Roebuck catalogs, but represses his feelings. Eventually, he sees an episode of the pioneering David Susskind Show, featuring a man from the Mattachine Society. The author’s path is clear; he must go to New York.

But once he lands, things are not as they appear. Robinson tells Segal that the group isn’t in tune with younger activists. This is one of the most important myths Segal busts: The gay movement was not unified and was segmented by, among other things, age and class.

About a month after Segal is in New York, the Stonewall Uprising happens.

Stonewall, notes Segal, wasn’t the first gay protest (it was preceded by the Compton Cafeteria riot in San Francisco and the Dewey’s sit-in in Philadelphia). It wasn’t as big as you might think (Segal estimates a few hundred participated). It wasn’t one night (try four). It was not about Judy Garland dying, and it only included a small representation of the gay population.

“[A]nyone with a decent job or family ran away from that bar as fast as they could to avoid being arrested. Those who remained were the drag queens, hustlers, and runaways.”

The movement Stonewall gives birth to results in a different kind of activism involving the media. Segal starts doing zaps, or “nonviolent protests that put us in a light that was not stereotypical.” In front of about 60 percent of America, he interferes with a Walter Cronkite broadcast. It’s a brilliant strategy, taking the weapon out of the hands of an oppressor and using it as a tool of activism.

Segal really puts the movement in context for the post-Stonewall generation. Activism in the 60s and 70s wasn’t about big corporations or celebrity spokespeople, he notes, and most gays didn’t appreciate the efforts activists were making. It also wasn’t the gig you took if you wanted to be a millionaire. Segal finally figures out a way to be paid for his activism by publishing the Philadelphia Gay News, which he still runs.

The flaws here are minor. Obviously, the death of his mother and the raising of his son are important to him, but they don’t translate into riveting copy, and his account of what it was like to help create the Philadelphia Freedom Concert & Ball, starring Elton John, feels pointless.

What Segal does best is provide an accessible history. And Then I Danced makes a great college textbook, or just an excellent guide for young queer leaders. The most important lesson one can learn from Segal’s life is that, no matter what, you just have to keep on fighting.

“And Then I Danced: Traveling the Road to LGBT Equality,” By Mark Segal, Open Lens/Akashic Books, Hardcover, 9781617754104, 400 pp., released October 2015.

The Gayly – January 16, 2016 @ 10:20 a.m.