"Othered”: Writer turns her oppressed childhood into positive work

Review by Stacy Pendergrast

To read Randi Romo’s Othered is to share both the grief and resilience of one woman who has been “othered.” As a Xicana, a queer, a sex abuse survivor, a former farmworker, an activist and a Southerner, her loved ones have likewise suffered.

This book of 28 poems features the kind of writing that can only be wrought from deeply-lived, traumatic experiences as well as from a lifetime of brave responses.

Romo is a woman of feeling and passionate words, but she is just as much a woman of action. Fifteen years ago, she co-founded the Center for Artistic Revolution (CAR) in Arkansas, an LGBTQ+ civil rights organization named by the marginalized kids whom she mentored and for whom she still fights.

Romo discussed her motive to make more Arkansans advocates for LGBTQ+ issues. “It’s true, there are some who will never shift, but it’s the greater movable middle that now finds itself increasingly having to consider the real impact of homo/transphobia on their fellow Arkansans,” said Romo in a 2015 interview with the Arkansas Times.

With her new collected works, perhaps Romo has lifted her voice in her greatest rallying cry for those whom she defends, and it is likely her message will reach far beyond her state.

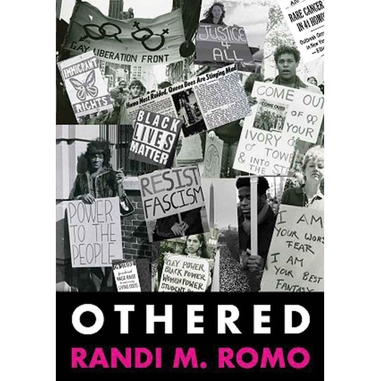

From the moment we view the collage of protest images on the book’s cover, we brace ourselves. In the introduction, publisher Bryan Borland prepares us further when he tells us how Romo writes on behalf of those voices which have been silenced.

Borland says, “Sometimes those voices belong to kids she’s had a hand in saving. Sometimes those voices belong to kids who couldn’t be saved, even with her best efforts. Tragically, two poems serve as epitaphs for two of those victimized for being different. Most heartbreakingly, Romo dedicates the book to her daughter “whose life was deeply impacted by the penalties of otherness and who paid the ultimate price with her life.”

Indeed, the poems deliver on our expectations to be disturbed. In “Coming Out” we learn the response to the young Romo’s revealed sexuality was for her to be sent away for gay conversion therapy, where even after she was put through “queer exorcisms.” Despite this, she proudly “stayed out.”

In “Planting Season,” Romo reveals the tragic plight of migrant workers (she was one) who are exposed to a deadly gas as they work the strawberry fields.

The poem “I Remember” gives us Romo’s wrenching account of how she endured multiple counts of sexual abuse, and how she learned to “sleep in boots jeans sharp-edged knife.” She effectively haunts us with the repetitive ending lines: “Not a one of these things happened in a public bathroom.”

It is as if this writer takes all those years of compiled suppression, bullying, and abuse, and — with the natural focus of a child who works a play dough squeeze machine — kneads her compacted clay of pain, then leans on the lever of language so her poems come oozing out, brilliantly colored and exquisitely molded.

The overarching theme of this collection is a victorious affirmation in the face of relentless oppression and violence. However, there is a tremendous range, and the reader is also relieved and brightened by Romo’s lighter tones, including her breaks for humor.

There is the playful “Bless Your Heart” from the perspective of the young poet, the child of a “Mexican mama and a white daddy,” who is both charmed and befuddled by the whimsy of Southern expressions.

In the fantastical “Step-Sister’s Lament,” the girl-narrator at Cinderella’s ball imagines her mother’s reaction to her being the suitor of a princess instead of a prince.

To our delight, we revisit our adolescent celebrity infatuations as we read “Fan Letter to Hedy LaMarr.” No matter the gender of the one we crushed upon, we recognize the fluttering thrill in the words of the teen moving toward her star on the TV screen. The poet says, “… so close I could touch you, and I wanted to, and it terrified me, and it exhilarated me, and I knew something was forever changed on a Saturday afternoon …”

Perhaps the flashes of quiet angst best highlight the gift of Romo. Indeed, where she shows us how she fights back against bigotry, we admire her guts and wonder if we could muster equivalent courage. But it is in the calmer universal moments she often appeals to our sense of sameness with her. After all, as social beings, we fear to be outcast or marginalized. This poet portrays pangs which strike deeply in all of us.

To purchase your copy of Othered, visit www.bit.ly/RRomo.

For more about Randi Romo’s life journey, click here.

Stacy Pendergrast is a teaching artist in Arkansas. In 2017 she was awarded the Nan Snow Emerging Writer Award given at the CD Wright Women Writers Conference at the University of Central Arkansas.

Copyright The Gayly – December 26, 2018 @ 7 a.m. CST.