What role for government in the obesity epidemic?

LIZ SIDOTI,Associated Press

WASHINGTON (AP) — Americans have always been conflicted on what role government should have in their private lives. The scale tilts wildly depending on the issue and the era.

Each day, people, courts and lawmakers wrestle with this constant tension: Where does government's duty to protect its people end and an individual's right to choose begin? And when someone's choice impacts society, how far is too far?

These questions are at the core of the national conversation over America's obesity epidemic, a private issue that's become more public as rates rise and stress our healthcare system.

Clear answers about the right private vs. public balance, as with so many things, will never exist. But the ways Americans prefer to tackle this public-health crisis offer clues about where the nation stands today. And as ambiguous as those views are, they may give our leaders guidance about how to constructively address other issues where the line blurs — education, guns, energy, gay marriage, marijuana use and the environment, among others.

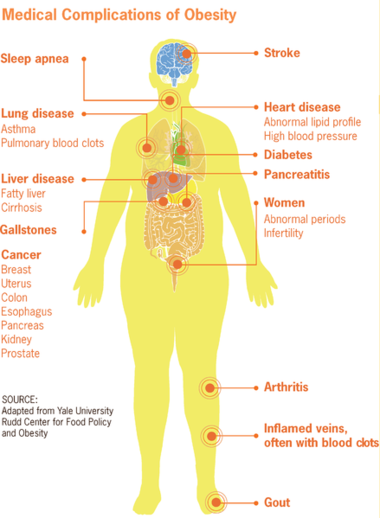

Obesity deals with a significantly personal issue — our bodies. But it also has a huge impact on society, given that skyrocketing health care costs are driven in part by the slew of avoidable medical problems it produces.

More than two-thirds of adults, and a third of American children and teens, are obese or overweight. It's one of the nation's top three killers, and it's on the rise.

Views on what to do about it are telling in their contradictions. While Americans are hardly monolithic about it, polling shows that people generally know there's a serious problem.

Most value personal choice over government involvement to address the crisis; in a recent survey by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, 88 percent said individuals bear the most responsibility. But many also see a role for other entities, including government, in fixing it.

To what extent is debatable.

Eight in 10 favor government policies that make it easier for individuals to make healthier choices, such as providing nutrition and exercise guidelines, and three-quarters support funding farmers markets and bike paths.

But people drew the line at government mandates, with more than half opposing taxes on soda pop or junk food, and three-quarters balking at restrictions on what they can buy.

Americans, polls suggest, want government to pave the way for them to make better health, fitness and nutrition choices by giving them tools, resources and access — without forcing them to do anything. Ultimately, they want to choose whether to use bike paths, shop farmers markets or select meals based on calorie counts.

Like in so many other areas of our lives, Americans want the benefits of government help but not the restrictions — give me the tools, then back off.

Even that isn't always a smooth road. First Lady Michelle Obama faced ribbing from critics and comics alike in 2010 when she rolled out her "Let's Move!" campaign to instill healthy habits in the nation's youngest generation.

Yet there was no serious controversy because the campaign focused on marshaling federal resources — and partnering with communities, businesses and schools as well as the entertainment and sports industries — to create awareness and provide information about healthy choices for children. "Let's Move!" is funded by government, but it doesn't force anyone to do anything.

But the Obama administration faced heat from critics, including congressional Republicans and parts of the food industry, over changes to the decades-old food pyramid nutrition guidelines. Same story when the Agriculture Department told schools to cut sodium in subsidized meals for low-income children by more than half, use more whole grains, serve low-fat milk and limit kids to one cup of starchy vegetables a week.

That seemed like nothing compared to the backlash New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg — a political independent who has made healthy initiatives a hallmark of his tenure — received with his move to restrict sales of large sugary drinks.

Soda makers, restaurateurs and other businesses sued to block the effort by the Bloomberg-appointed health board. Ten City Council members called on the health board to scrap the rule, and a New York Times poll showed that six in 10 people opposed it in New York — a bastion of liberals who tend to tilt toward bigger government.

Bloomberg's health department has already banned artificial trans fats in restaurant meals and compelled chain eateries to post calorie counts on menus. Now he is trying to banish sugary and fatty foods from public and private hospitals, also stirring controversy.

Critics usually accuse governments that tell people what to do of running a "nanny state." It's nothing new; American history is filled with government efforts to shape personal behavior.

Among the most notable: Prohibition, which from 1920 to 1933 barred making and selling alcohol. Congress repealed the law after it became clear that banning booze didn't curb many social problems.

—Four decades ago, the federal government required states to enact laws requiring motorcycle helmets in order to get highway construction funds. Much griping ensued. The government also started requiring seatbelts in vehicles around that time. Two decades later, New York became the first state to pass a law requiring people to wear them. The hue and cry over that, too, eventually passed.

—By the 1990s, state and local governments had started to rein in public smoking. Controversy flared, but eventually largely fizzled.

—The most contentious debate between public v. private — abortion — rages on, but it's different in one fundamental way: Many contend that issue is about someone else's health, not only your own.

What does this all teach us, other than what we already know — that Americans are generally suspicious of being told what to do?

Those who would regulate more could take refuge in the fact that, for the most part, the outcry fades after a law becomes common practice.

And the regulation-wary can learn, from the obesity debate, that government can, at times, adeptly balance the instinct to control with the ability to facilitate solutions. What might that look like when applied to today's most contentious topics — to education, to energy, to the environment, to gun control?

In the public's mixed attitudes about the obesity epidemic, we find a signal to our leaders: Government can stake out effective territory when it provides individuals with what they need to make their own choices.

Whether this model works to lower obesity rates remains to be seen. Consider that 65 percent of people in the AP-NORC poll identified a major reason for the obesity problem as a straightforward one: People don't want to change. Americans have to make the personal decision to live healthier lives or they'll simply ignore the resources available.

In the end, if government goes for the nudge rather than the outright shove, and we choose poorly, the only people to blame will be ourselves. Which, conveniently, is what many Americans say they want — the ability to rise and fall on their own, without the people who represent them getting in the way.

___

EDITOR'S NOTE — Liz Sidoti is the national politics editor for The Associated Press.